Of Desert Peaks Not Normally Climbed in Summer

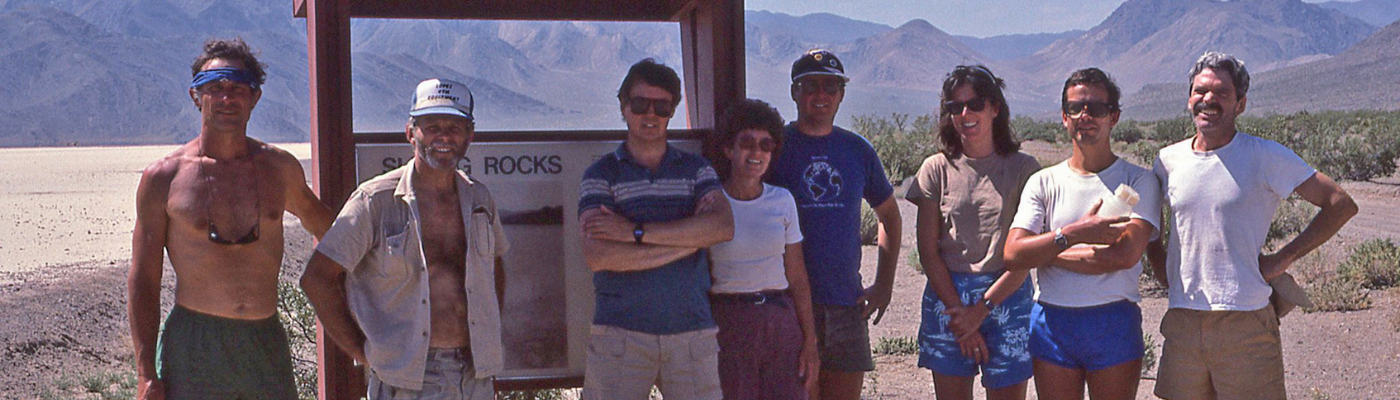

DPS Group hikes Tin Mountain, 1985 (Wynne Benti pictured third from right)

Brief History of the Desert Peaks Section

Wynne Benti is Editor of the Desert Sage (Desert Peaks Section, Angeles Chapter), a member of the CNRCC Desert Committee, Military Expansions (NTTR, FRTC) and has been a Sierra Club Life Member since 1985

Add new comment